By Mary Freitas

In a special Latta Edition of The Dillon Herald, March 29, 1923, the following interesting information was given of the Latta Schools.

The Latta School, first known as Vidalia Academy was organized in 1879, and was held for some years in a dingy one-room building.

From the best information to be obtained, the first men connected to the school as teachers were Dr. Wade Stackhouse, Mr. P.T. Bethea, Mr. L.H. Smith and Mr. W.P. Rankins. During the last two years of the academy, Mr. Nickles, who was afterwards Superintendent at Dillon, and later went to Greenwood, was principal.

As the town grew, the need became pressing for a larger building. In order to meet this need, the Latta Educational Society, in 1879, built a three- room wooden building, which later was increased to five rooms. From 1899 to 1902, Mr. C.M. Staley was principal. He was followed by Mr. C.C. Goodgion, who was principal for three years. In 1905, Mr. H.W. Ackerman was elected and held the position for four years.

It was during this time, the fall of 1906 that the old wooden building was destroyed by fire. A new grammar school building was erected and was occupied for the first time in the spring of 1907.

A Mr. Bauknight became Superintendent in the fall of 1912, and under his faithful and efficient administration, the school grew into one of the best in the state. The little ungraded school of a few short years before now became a real 11th grade high school and was one of 23 schools in the state recognized by the Association of College and Secondary Schools of the Southern States.

In 1914, a separate high school building was erected, which, together with a new workshop, gave ample room and facilities for all school purposes.

Mr. R.T. Fairey became superintendent and the school grew with over a 90 percent enrollment—40 pupils in 1918 to 78 in 1923, Latta became a real school when the students above the 7th grade from Sellers, Dalcho, Oak Grove, and Dothan Schools were brought in after consolidation.

Mr. B.F. Carmichael succeeded Mr. Fairey in the fall of 1923. During his administration, the schools expanded and many new features and aggressive policies kept Latta in the forefront in the county.

One of the first innovations was the semi-monthly school paper, “The Latta Shall-Go,” was the first in the county and was a great builder of school spirit. Mr. Olin Epps, a retired school teacher, principal, once had a framed copy of this school paper hanging in his house in Latta.

Vidalia’s Story

In Fact And Legend

Compiled by

Mrs. Elizabeth B. Monroe

And reprinted with permission

Preface

How often have the words been spoken, “If old buildings could speak, what stories they might tell!” In the following work some of the tales Old Vidalia might tell have been gleaned from the personal recollections of several of her former pupils and from stories handed down to relatives of her founders and her pupils.

Appreciation for all this information, factual and legendary, goes to Mrs. Florence Henry Bethea, Latta, S.C.; Mrs. Argent Bethea Gibson, Dillon, S.C.; Mrs. Carrie Monroe Epps, Latta, S.C.; Mrs. Carro Henry Pfaff, Winston-Salem, N.C.; Mr. Daniel W. Coward, Latta, S.C.; and Mr. Henry W. Allen, Latta, S.C., who were kind enough to allow me to go sit, listen, and take notes as they unraveled these memories of years gone by.

Vidalia came into being because of a father’s desire for a school close to home for his children. This father was Mr. Herod W. Allen, whose farm lands covered hundred of acres a few miles east of the present town of Latta.

Mr. Allen chose a site almost at the top of a hill about two miles from the heart of town and about seventy-five yards in front of the present site of the Joe White home, close to what is now Highway 917.

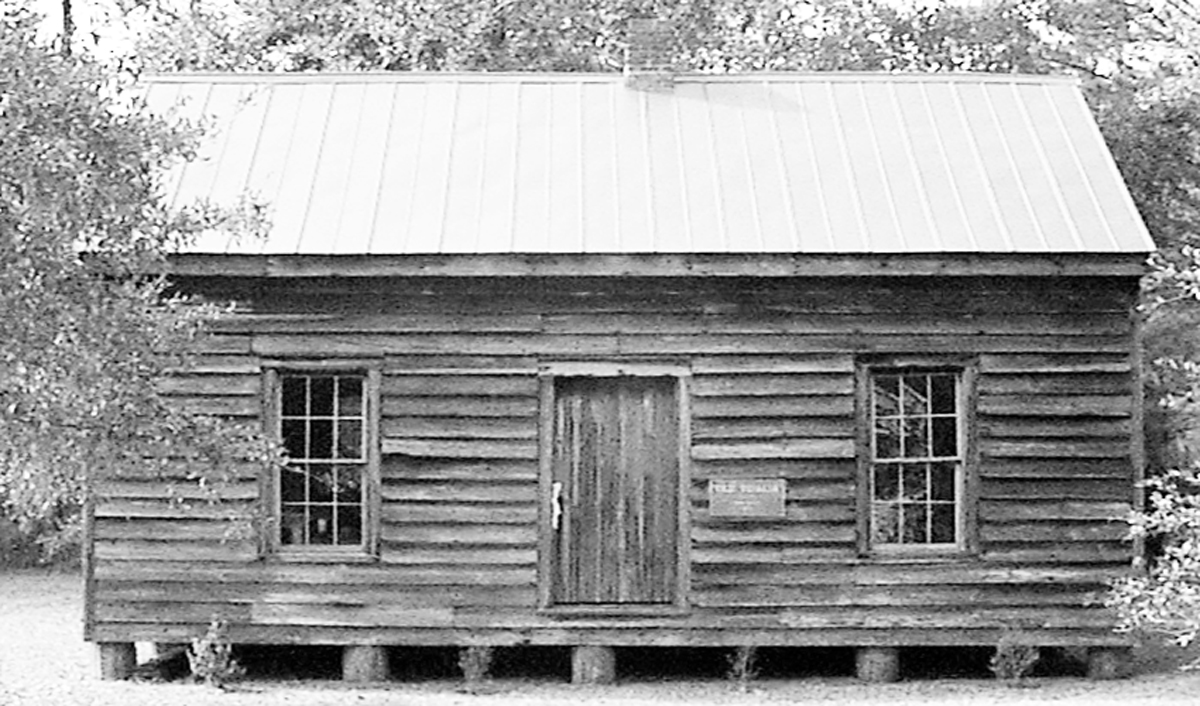

With the help of farm laborers, he hewed the logs* and built the school himself. It was completed around the year 1877 – a sturdily built one-room schoolhouse with the chimney in the center. There was only a sand and clay floor to the building, and the children sat on benches.

When the school first opened, there were fifteen pupils in all. Besides the Allen children, the others were children from the neighboring farms. Among these were several of Dr. Francis Marion Monroe’s daughters (Annie, Betty, and Daniel); Mr. Sam Watson’s older children; Mr. Harland Lane’s children (Frank and Willie Allen); and Maggie Williams, who lives with Mr. Mack Martin’s family across from the cemetery.

The pupils paid $3.50 a year as tuition. One of Mr. Herod Allen’s sons was not old enough to go to school, but the older Monroe girls agreed to look after him so that the enrollment would be high enough to enable the school to qualify for State Aid. One of the Monroe girls, Betty, was allowed to attend at age five for the same reason.

In 1879, the school was moved to a new site on the opposite side of Latta to the north and diagonally across Highway 301 and the Seaboard-Coastline Railroad from the present site of Latta High School. Dr. F.M. Monroe had offered to donate four acres of land for the relocation of the school. He felt that this new location would attract more children and enable the school to grow.

Mr. Allen consented to the moving of the school provided Dr. Monroe was able to accumulate three more votes than Mr. Allen. Therefore, in 1879 the school was moved. Dr. Monroe furnished wagons and hands for the reconstruction of the building. Mr. George Bethea and Mr. Herod Allen helped with the tearing down and moving.

*A broadaxe was used to hew the logs. This broadaxe had been used by Mr. Herod Allen’s father, who died in the woods with the axe in his hand. His body was not discovered until sometime after his death. –This occurred a short time before the school was built. The axe was donated to the Vidalia Museum by Mr. Herod Allen’s son, Mr. Henry W. Allen.

For years a pile of sticks and clay, evidently from the old chimney, stood on the hill at the Allen farm where the schoolhouse once stood. However, when the horse-drawn plow came, these last remains were scattered over the field, and today the old site can no longer be definitely located.

The first trustees of Vidalia were Mrs. Lucy Bass, Mr. T.J. Bass’s grandmother; Mr. D.E. Watson, Messrs. Hal and George Watson’s grandfather; Dr. F.M. Monroe; Mr. Herod Allen; and Mr. Mack Martin.

For a time Vidalia remained a one-room building, but now it did have a wooden floor. Later, as the enrollment increased, a second room was added. This made it possible to separate the primary children from the older boys and girls.

At this time, parents paid tuition according to their children’s level in school. The price for children in the primary group was so much; the price for the children in the upper group was higher, and it was still higher for those taking Latin and Algebra. The money was used to pay the teachers.

The teachers boarded at the home of Dr. Monroe. Mr. James Baker and Mr. Charlie McLean were two of the early teachers. Mr. Baker later married Dr. Monroe’s daughter, Annie. Mr. McLean taught at Vidalia four years. Other teachers included Mrs. Lenore, who was very frail and had small children of her own; Mr. Lon Smith; Mr. W.P. Baskins, who taught the older children at the same time that Miss Betty Monroe was teaching the primary children in the back room; and Mr. W.W. Nickles, who also taught at Vidalia for four years.

The story is told that on occasion that Mr. Baskins dated Miss Betty Monroe. At school she called the rolls for his class and hers. The first name on the roll was Betty Allen. One morning, he inadvertently called “Betty Monroe” instead of “Betty Allen.” This caused much merriment among the pupils.

A typical school day at Old Vidalia resembled only in a small way a day in our modern schools. The teacher rang a large hand bell to signify that it was time for classes to convene or for recess or to end. The day began with devotions and songs. There were no grades as such. The pupils advanced according to their abilities. The teacher taught one class at a time, and the rest of the pupils would study. For instance, while those taking Latin were reciting, the others would study their assignments for their next class or for the next day.

On Fridays, the whole group joined in the weekly spelling match. Two leaders would choose sides, and they would keep spelling until only one was left undefeated. Often the match would have to be continued until the following week. Mr. Horace Bethea was known as one of Vidalia’s best spellers.

Also on Fridays, every pupil was required to have learned a speech, poem, or otherwise, to recite before the school. Mrs. Argent Gibson recalled that her mother found and cut out for her “The Night Before Christmas,” and she recited this during the Christmas season. After that, she was called on to recite it over and over throughout the year.

The pupils wrote their lessons on slates with a hard, slender pencil made especially for this purpose. The schoolroom blackboards were made out of painted boards built on legs. At first, pieces of sheepskin were used for erasers. These cleaned the boards well. When one wore out from use, the teacher would ask for volunteers to bring more. Many people in the community raised sheep, and they were glad to donate pieces of sheepskin for this purpose.

The children, mainly the girls, kept the blackboards washed and cleaned. They considered it an honor to be asked to wash the blackboards, and they gladly came in early or stayed after school to do this.

The school was heated by a long, slender stove in which wood was burned. Dr. Monroe gave them permission to thin the woods around the school to get wood to burn. The boys went early and cut the wood and made the fires. They would build huts to play in out of the tree tops. One day, in about 1895, some of the “devilish” boys set some of the tops afire. The wind came up, and it was only by a great deal of effort that the whole winter supply of firewood was not destroyed. The teachers and larger girls had their hands full trying to keep the smaller children away from the fire.

Sometimes during the school day, the boys would jam more wood into the stove, and after it began to burn in earnest, they would open the door quickly. This would cause a draft, and the result was a loud “puff-puff” sound, which delighted the boys. They pretended it was a steam engine, and they made quite a lark out of it.

The girls dressed neatly, but quite differently from today’s little girls. They very often wore the same dress to school for a week, but they wore aprons over their dresses.

These aprons were changed on the average of twice a week, sometimes more. Some of the aprons were very fancy and pretty.

Mrs. Argent Gibson remembered one her mother made for her with brown lines and red embroidery on it. Others were white and frilly or plain and tailored, but they were always starched and clean. Most of the boys wore knee-length pants and long stockings in the wintertime. In the spring and early fall, they more often went barefooted.

Before school took in, in the mornings and at the long recess, the children enjoyed playing together in the large school yard.

There was no grass in the yard, but it was kept swept spotlessly clean. One of the accepted and expected chores of the children was to sweep the front yard. They did this with brush brooms made sometimes of broom straw, but more often of leafy branches broken from nearby bushes and tied together to make a broom.

The boys and girls enjoyed playing all sorts of games. Some of the games, like baseball, they played together. The ball and bat were homemade, but they served as well as modern high-priced ones. The baseball was made of raveled cotton stockings and was sewed together with needle and thread. Sometimes, some rubber was put in with the string. The bat was a heavy piece of board trimmed down to a handle. A tree that was divided near the ground and was called “the two-legged” tree by the children, was used as a base.

At the lunch recess, the girls liked to go to the edge of the woods and make play houses in the pines. Mrs. Florence Bethea remembered how they used to mark off the rooms and improvise household furnishings out of all kinds of pieces of wood, broken glass, sticks and such. They made hats out of oak leaves and added wild flowers and broom straw for trimming.

While the girls built their play houses, the boys played horseshoes in another part of the yard. Horseshoes were plentiful, because horses were the chief means of transportation, and every boy could find several spare horseshoes around the stables at home.

Another favorite game of both boys and girls was see-sawing. The see-saws were made from the trunks of cut pine trees. The children brought boards from home to go across the trunks. Flying jennies were also made from wood. These were more dangerous than the see-saws, and the children often fell off.

At times, tops became the game of the hour. These were made from spools. It was quite a sport to see whose top could spin fastest and longest.

Besides finding much joy in playing and romping in the school yard, the children delighted in eating their lunches together and sharing them with each other.

Their lunches were prepared at home and taken to school in baskets, and most of the boys took theirs in buckets.

Some would carry molasses in bottles and bore holes in their biscuits and fill the holes with molasses. The boys would often pour the molasses into their bucket lids and sop it up with their biscuits.

One lunch favorite was a big, cold, boiled Irish potato. Another favorite was green peppers stuffed with cabbage pickle. They also carried biscuits of sausage, ham, jellies, or other homemade delicacies. As soon as the recess bell rang, the children would scatter with their lunches into small groups over the yard and into the edge of the woods. Everyone was anxious to see what their friends had brought and what they wanted to swap with them.

Drinking water was supplied by a well, which was located on the north side of the schoolhouse. The well was made with a long pole used as a sweep. From the upper end of the sweep, a smaller pole extended down, and the bucket was attached to the end of it. To draw the water, one or two of the boys would lower the bucket pole down into the well.

When the bucket was full, they would raise it with the help of the sweep. They had to hold the smaller pole to prevent the sweep from raising the bucket too fast.

There was only one good dipper for all the children, and they had to take turns about drinking from it. Once in a while, a frog would be drawn up in the bucket of water. They would simply throw him out and keep on dipping and drinking.

Later, a pump was installed at the opposite end of the school yard. This replaced the well as a source of water, but the well remained on the grounds for many years.

Besides helping with the school chores and indulging in play between lessons, the boys often found time for mischief and escapades common to most boys. They carved names and initials on the desks, cut cross-vines and made cigarettes, and then lit them and tried to smoke them.

They also had their disagreements and fights. One such fight that most of the “alumni” remembered turned out to be a rather gory affair. It seems that one devilish, barefooted boy stuck a straight pin through the tough skin of his big toe. He straightway used the new-made weapon to prick his “pal” sitting in front of him. This infuriated the “pal,” and he swished out his knife and began hammering his friend’s head with the closed knife until the blood began to fly. The teacher stopped the fight in the only way that seemed plausible at the time. He poured a bucket of water on the two struggling boys. This ended it!

Mr. Dan Coward recalled that when he was a pupil at Vidalia, the trains passing by near the school were a real novelty. From his seat, he could not see out the window to watch the trains. However, he could reach a knothole in the weatherboarding with his knife. The idea no sooner struck him than he acted. He cut the knothole out of the wall. Then, he had a perfect view of the tracks, and every train on them. Luckily, the teacher did not catch him, or he might not have found this pastime so interesting!

There was another adventure of the boys where the trains were concerned. Walking to and from school, many of the children walked down the railroad. At one point, the tracks were built upon a tressel. The boys delighted in crawling beneath the tressel and waiting for a train to pass over them. Thus, they were being run over by the train. Incidentally, many of these children walked as far as three miles to school every day.

The boys, especially the older ones, took an interest in the girls. The early days at Vidalia were not without romance, even though the girls and boys were perhaps shyer and more subtle about it than our present-day young people.

Little cards and small pieces of paper with verses written on them, such as, “Roses are red, Violets are blue, Sugar is sweet, and so are you,” were slipped to the girls. These caused many blushes, but they often led to courtship and finally marriage.

According to Mrs. Carro Henry Pfaff, the participants were the fathers and mothers, grandfathers and grandmothers of the young adults and young people of the Latta community today.

Along with the happy times at Vidalia, sad times came too. There were so few pupils that when any moved away, they were sorely missed. When the family of Mr. John C. Bethea moved to Dillon, this brought sadness to all the Vidalia pupils and teachers alike.

This meant the less of Argent, Horace, and Octavia, who were not only popular playmates, but were also among the best students.

Their home had been where the T.J. Squires’ home is now. The morning they moved, the children stood at the windows of Vidalia and sadly watched the wagons taking them down the old road to Dillon. The school was just not the same without them.

The school year at Vidalia always ended with an annual picnic. There was always food in abundance, all kinds of cakes, pies, chicken, and country ham. The people brought all these good things to eat packed in small wooden trucks. Lemonade for the occasion was made in big wooden tubs. This gala event was eagerly looked forward to from one year to the next.

It might also be of interest to the reader to know that Vidalia was used for other purposes besides a school. Mrs. Carrie M. Epps related that the first Sunday School in Latta started there. Mr. Murray, a Methodist preacher, came from Little Rock and held meetings in the building.

Mr. Pierce Kilgore came from Little Rock and preached his first sermon at Vidalia. Just as he really began to preach, a puff of wind came in and blew his notes out the window. He never forgot Vidalia!

In 1898, Vidalia’s enrollment had increased beyond her capacity to cope with it. A new three-room building was erected where the Emory Edwards’ home now stands, and Vidalia, as a school, was closed forever.

From this time until around 1950, the building was used a dwelling for families who sharecropped the land. Once during these years, tragedy struck in the old house. A murder was committed. The story goes that a man by the name of Jacobs lived in the old school house. His sister came to stay a while, and a man came to call on her. Jacobs did not want him to go into the house, but he finally told him he could go in if he would not cause a fuss. He went in, and Jacobs’ sister became frightened and hid under the bed. Whereupon the visitor pulled out his pistol, but Jacobs had had time to get his gun. He shot the visitor’s brains out. The blood stains remained in the floor for years afterward.

From 1950 until 1965, the old schoolhouse was vacant and fast lapsing into decay, mute evidence of the mass exodus from the farms. It and the land on which it stood were the property of the M.M. Monroe family. (Mr. M.M. Monroe, who died in 1953, was the son of Dr. F.M. Monroe and had become owner of the property as part of the settlement of the Monroe family estate.)

Mr. John Walker Bethea and Mr. Daniel B. Shine, Jr. began dreaming of rebuilding Latta’s first school and preserving it as a museum for the present generation and for generations to come.

Mrs. M.M. Monroe, her son, James G. Monroe; and her daughter, Mrs. P.M. Mitchell; gladly consented to donate the building for this cause.

The building was moved to the Latta High School campus in the early party of 1965 and has been restored as nearly as possible, inside and out, to the original one-room schoolhouse of 1879.

In some moments of leisure, it might prove interesting to go and sit quietly in one of the old rough seats and dream awhile of the stories of Old Vidalia told here and of others still untold. The restoration of Vidalia is a fitting memorial to those both living and dead who were pupils. It is also a fitting tribute to progress.

As one views tiny Vidalia in the midst of Latta’s 3 city block complex of school building the following comes to mind. Great oaks from—.

“Great oaks from little acorns grow and still keep growing then.”

Editor’s Note: As many know, Vidalia Academy became the property of A. LaFon LeGette, Jr.,in 1966 and now stands in the Veterans Park in downtown Latta. It is sometimes opened during special events so people can go inside and take a look.